LEADVILLE, COLORADO – Armin Gooden was four years old in 1983 when the once-booming mining town of Leadville, Colorado – on the verge of economic devastation after the closure of Climax Mine in 1982 – hosted the first-ever Leadville Trail 100-mile run.

Race founder Ken Chlouber had organized the trail run in what’s considered North America’s highest incorporated town, elevation-wise. He hoped it would salvage Leadville from virtual ruin after more than 3,000 workers were left unemployed in the wake of the mine’s closure the year before.

On Saturday, Aug. 17, Gooden will be four decades old when he tries his hand – well, legs – at the iconic 100-mile course which snakes 50 miles out and back through the Colorado Rockies. Terrain is comprised mostly of forest trails with a few mountain roads mixed in, its website says.

Gooden, whose 40th birthday fell on this past Sunday, is a 1997 graduate of Buckhannon-Upshur High School. His mom, Idress, and dad, Dave, still live in Upshur County.

But they’ll be in Leadville at 4 a.m. sharp Saturday, when the race begins. The Leadville 100’s lowest point measures about 9,200 feet and its highest peak 12,600 feet. That point is known as Hope Pass – or ‘Hopeless Pass’ by runners “because it crushes souls and destroys dreams,” Gooden says. In fact, a local CBS station out of Twin Lakes, Colorado, on Thursday reported that a 28-member team of llamas and their human guides hauled approximately 3,000 pounds of food, drinks and gear up to an aid station at Hope Pass.

Gooden good-naturedly called the race his “mid-life suffer-fest” Wednesday in a Facebook post when he thanked his friends on social media for their recent birthday wishes: “Thanks for all the birthday wishes! Stay tuned for live tracking at my mid-life suffer-fest in just a little over two days,” he wrote.

The primary question that runners who do ultra-marathons– especially hundred-mile ultra-marathons – face is: “Why?” Why subject yourself to such a “mid-life suffer-fest,” as Gooden put it? After all, only about 50 percent of runners who qualify through the lottery actually complete the Leadville 100, Gooden said. Others must drop out if they don’t make various cut-off points throughout the course, including completing the first 50 miles in 14 hours or under.

(For non-runners, ultra-marathons are races longer than the 26.2-mile marathon and can vary in distance from 32 to 50 to 100 miles.)

For Gooden, who’s now a resident of a Denver-area suburb, the thirst to complete the Leadville 100 began as a mode of mental survival.

“I had a really rough year in life the past year-and-a-half,” Gooden said. “I did this huge climbing trip in Alaska at Denali National Park, and I sort of cheated death after surviving this crazy storm. I had gone through a really bad divorce, and I was in no mental space to run, but I needed some kind of outlet.”

“A good friend of mine knew I wasn’t in the best place, so he said, ‘You’re going to start running again, and you’re going to pace me in the Leadville 100,’” Gooden recalled. “Life just kind of gave me what I needed.”

Pacing his friend in the 2018 Leadville 100 – for a 14-mile section from miles 62 to 74 – was enough to hook Gooden.

“It was pretty awe-inspiring,” Gooden said. “I muled for him. I carried all his water and food. It really allows you to experience team camaraderie. I knew right then and there – I decided, ‘I’m doing this next year.’”

Of course, it wasn’t exactly Gooden’s first rodeo when it came to running.

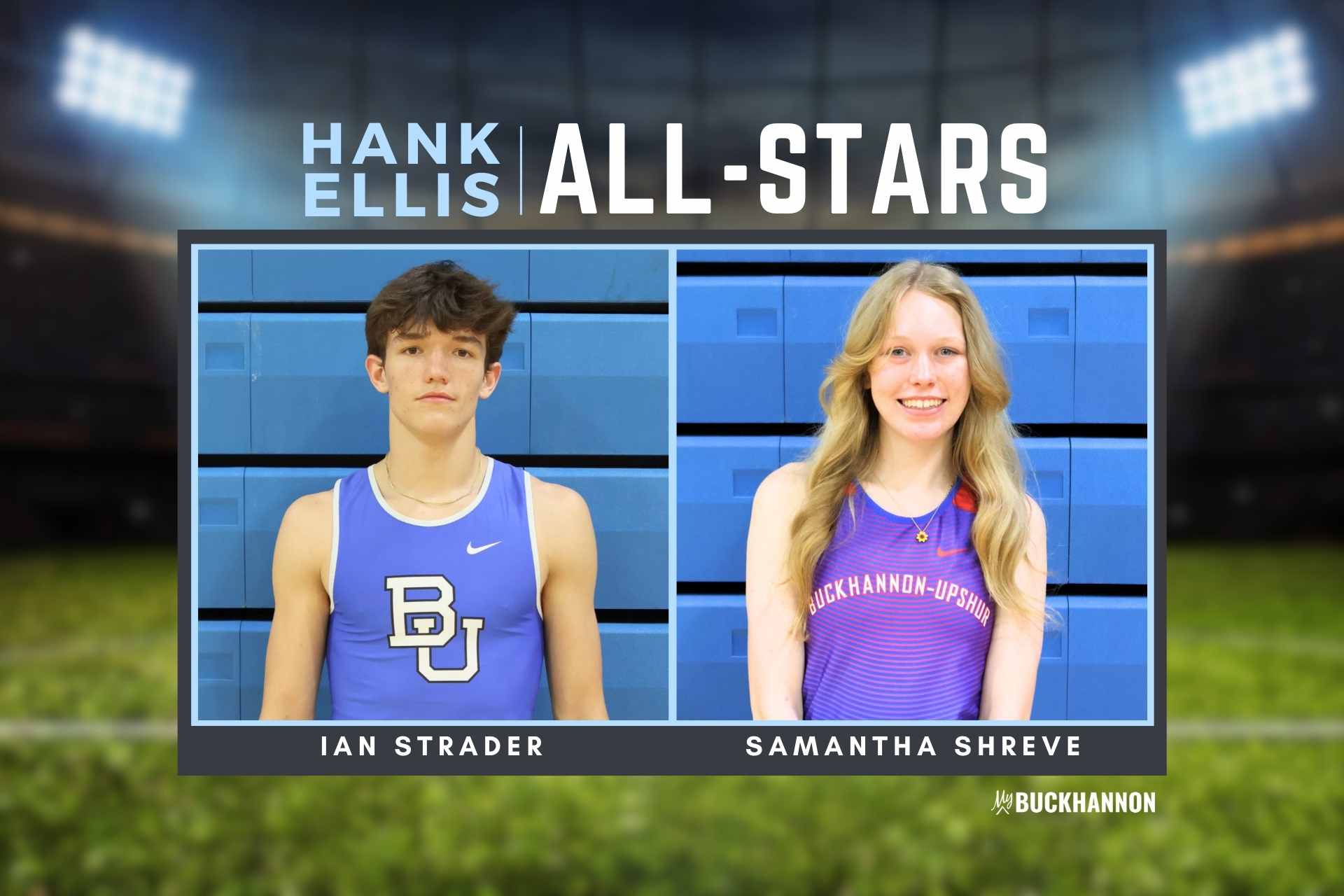

He was a standout cross-country and track and field runner in high school who was recently inducted into the Buckhannon-Upshur High School Athletic Hall of Fame as a member of the school’s undefeated state champion cross-country team in 1993. Gooden went on to run at Frostburg State University in Maryland. However, his college career ended when he was plagued by persistent lower back pain.

“I actually quit running in college because I had so much lower back pain,” he recalled. “I can go for a seven-hour run now and have no lower back pain.”

Combined with natural running talent, Gooden, who works as an emergency room nurse, has always had an appetite for adventure. In addition to Denali National Park in 2018, he’s also mountain-climbed in the Peruvian Andes and Island Peak in Nepal. He completed the Grand Traverse Ski Mountaineering Race from Aspen to Crested Butte, Colorado, as well as the Dirty 30 50K – about 31 miles – in June 2019, too.

In addition to why, another common question he faces is: “How?”

How does one go about training for a 100-mile race with elevations so high that most people – even skilled runners – average, at best, about 15 minutes a mile? As Gooden explained, he’ll likely “power-hike” steep sections of the race that are above a 5 percent grade.

“On the Leadville course, I’ll probably end up running about 70 miles and walking or power-hiking 30,” he said. “If you finish in under 25 hours, it’s kind of insane and you get a big gold belt buckle.”

But it’s taken Gooden awhile to come to terms with not going all out for the whole race. In fact, it took hiring a coach who was able to “reel him in,” he said.

“Anything I do, I do full bore,” Gooden explained. “I don’t do anything half-[heartedly].”

“In November (2018), I was doing about 50 miles a week and at a half-marathon pace at seven minutes a mile,” Gooden said, “and a good friend of mine said, ‘You need to get a coach.’ And it’s true – you can kind of be your own worst enemy by training too hard. So, my coach said, ‘Armin, you need to slow down. You’re training at a pace that would set the course record,’ so he taught me about the importance of holding back some.”

The course record was set in 2016 by a Colorado runner named Matt Carpenter, who traversed Leadville’s terrain in 15 hours, 42 minutes and 59 seconds. The record for women was laid down by 33-year-old Ann Trason, who finished the race in 18 hours, 6 minutes and 24 seconds in 1994.

The trick to training for a 100-mile race when it comes to logging enough miles is doing back-to-back long runs to simulate the feeling of tired legs. For instance, Gooden said one day he might run 32 miles, and then complete 20-some miles the next day.

“It works because you’re running on tired legs, but you’re not getting the stress of doing a 50-mile run,” he said.

Of course, moral support from carefully picked pacers is another key to conquering the course. Pacers are permitted – only one at a time – after mile 50. They typically join runners at aid stations. Gooden has three, and they’re all close friends and fellow athletes who know what to say – and what not to say – to Gooden at specific points in the race regarding pace and nutritional intake.

“They’re close friends who know me really well and motivational friends who tell me what I need to hear and not what I want to hear,” Gooden said. “Each person has their own qualities and styles of motivation that will work. I’ve never planned out something so much in my life. I want to succeed and I will succeed.”

As far as gear goes, runners are permitted to drop extra pairs of shoes and changes of clothes off at various points along the course in sealed plastic bags. Gooden says he plans on only wearing two pairs of running shoes – Hokas – but he’ll have attire ranging from full sun-protective clothing to warm running tights and gear that includes premium running socks and, of course, anti-chaffing ointments.

While a runner might be able to make it through a lesser distance like a marathon without ingesting solid food, Gooden says he’ll be eating Cliff bars and a variety of gels, some of which can be mixed with water. One includes the carbohydrate-packed Maurten hydrogel that allows athletes to ingest up to 320 calories at a time. Pickle juice to prevent muscle cramp is on his list, too.

Ultimately, the race is a test of physical and mental fortitude.

“The mental is actually the biggest part,” Gooden said. “I’ve done lots of power meditation and visualization training, visualizing almost every section of the course from start to finish.”

After all, it’s not just another race. For Gooden, what started as a coping method morphed into a meditation on strength, courage and gratitude. He’ll be repeating plenty of “warrior” mantras, including, “I am unbreakable” and “Run like it’s your last day on Earth,” he said.

“I’m training for life,” Gooden said. “This is not simple motivation; it’s all about drive and heart. I was going through a really rough time in life, and I needed a purpose. It’s about really being present and aware and having gratitude that I’m doing something so many people would kill to be able to do and to be in my shoes.”

“So, when I’m running at 4 in the morning and it’s cold and it’s raining, I’m just going to embrace it,” he added. “I want it to be colder, and I want it to rain harder.”

You can track Gooden’s progress live Saturday here.