A patient walks into an emergency room in rural West Virginia and complains of confusion, facial numbness and a severe headache. The doctor, suspecting a stroke, has to make a quick decision: should she treat the patient herself, or should she have the patient transferred to a stroke center an hour away staffed with specialists?

West Virginia University’s telestroke program makes this decision easier. It connects rural hospitals throughout West Virginia—and across the Maryland border—with neurologists at WVU, who can offer insight into stroke cases. New research suggests that since the program’s launch in 2016, more patients at those hospitals are receiving prompt, noninvasive stroke treatments there, rather than being driven or flown somewhere else.

With WVU’s telestroke program, doctors at rural hospitals can use technology to talk to, hold video conferences with and securely share medical records with neurologists at WVU. By working together, the healthcare team can diagnose strokes more quickly and determine the best course of treatment.

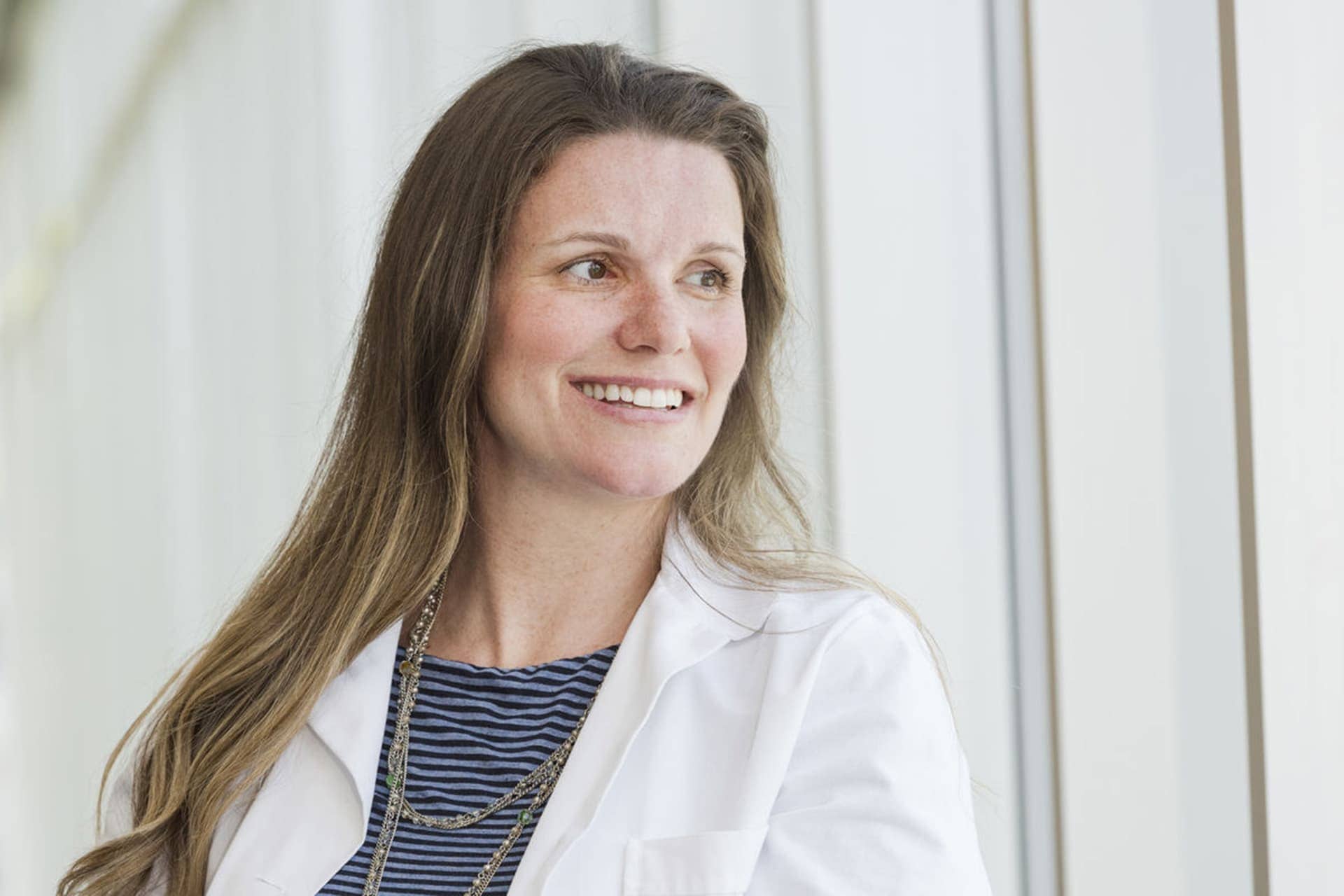

“We’re not here to dictate what doctors do,” said Amelia Adcock, the associate director of the WVU Stroke Center. “We’re here to lend a hand if they want it—especially in those borderline cases—to say, ‘Yes, this does look like a stroke. This person is eligible for treatment with this drug. Have you considered it? What are your thoughts and concerns if you don’t want to use it?’ There’s somebody there to bounce ideas off of.”

She and her colleagues analyzed data from eight hospitals that participate in the telestroke program:

Camden Clark Medical Center in Parkersburg.

Davis Memorial Hospital in Elkins.

Berkeley Medical Center in Martinsburg.

Fairmont General Hospital in Fairmont.

Garrett Regional Medical Center in Oakland, Maryland.

Potomac Valley Hospital in Keyser.

Raleigh General Hospital in Beckley.

Reynolds Memorial Hospital in Glen Dale.

They also derived data from the West Virginia Office of Vital Statistics and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which report stroke-related hospital discharges and deaths from across the state. Finally, they referred to the American Heart Association’s Get with the Guidelines Stroke Data Registry for national stroke metrics.

They found that between 2016 and 2018, the proportion of telestroke patients who received tPA—a stroke medication that breaks up blood clots—grew at the eight hospitals they considered. In 2016, only 19 percent of telestroke consults were treated with it. By 2018, 27 percent were.

TPA is the only noninvasive treatment that the Food and Drug Administration has approved for ischemic strokes, which accounts for about 87 percent of all strokes. But for tPA to work, doctors have to use it within four-and-a-half hours of symptom onset. If a patient has to be driven or flown from one hospital to another before receiving treatment, that window may close.

They also found that between 2015—the year before the telestroke program took effect—and 2018, the total number of stroke patients receiving tPA at the hospitals increased dramatically—from 259 to 448—while the overall number of stroke patients evaluated remained relatively stable.

“Acute ischemic stroke is one of those time-sensitive examples where access to specialists can make the difference in actually getting people treated,” said Adcock, an associate professor in the School of Medicine who directs the Center for Teleneurology and Telestroke.

When Adcock and her research partners crunched the numbers, they discovered that telestroke consultations facilitated local care—and made transfers unnecessary—65 percent of the time.

One reason ER doctors may hesitate to use tPA is their concern that it will cause hemorrhaging. Albeit rare, bleeding is one of the drug’s most feared side effects.

“Many emergency medicine doctors I’ve talked to on the phone are wary of the medication causing harm,” Adcock said. “They’re worried it will cause a bleed.”

But her project suggests the risk of hemorrhage is actually quite low for telestroke patients. Between 2016 and 2018, only three of the 292 telestroke patients who got tPA experienced a symptomatic hemorrhage. That’s about 1 percent.

Another reason for ER doctors’ reluctance is that diagnosing and treating stroke can be flat-out intimidating.

“Unfortunately, stroke garnered a reputation of being difficult to figure out,” Adcock said. “A lot of doctors who aren’t neurologists feel uncomfortable saying if this really a stroke or if it’s something else.”

She hopes that—with time and experience—more ER doctors will come to trust their own judgment when they treat patients who have slurred speech, sudden paralysis, loss of coordination and other signs of stroke.

Citation

Title: Expanding acute stroke care in rural America: A model for statewide success

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0087

Link: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/tmj.2019.0087